This piece was originally published on Every in March. The version below is a slightly less polished, somewhat longer, marginally unfinished draft—it feels more authentically mine :)

What made Myspace such a vibe? A coding error.

Myspace—one of the internet’s first third spaces—spawned out of the L.A. indie music scene in the early 2000s. Replete with different ways to establish your online presence, including sharing videos, writing blog posts, and uploading audio, the platform was a kitchen sink of social features.

But what made Myspace really sticky was that you could stylize your profile down to the very code, using custom HTML/CSS to personalize what you shared along with how it looked on your page.

These user-generated markups weren’t originally supposed to be part of the platform’s core functionality. There’d been a lapse in engineering (wo)manpower at the time, and the team forgot to block users from adding their own backgrounds and designs. Overnight, users started exploiting the leak, changing wallpaper colors and uploading “hearts and glitter and smiley faces the same way that [they would] decorate their lockers and book bags,” CNET staffer Zachary McAuliffe wrote in a 2022 Myspace retrospective.

“I even remember adding a cartoon dog named Lightning to my page that visitors could interact with by giving the pooch virtual treats.”

After seeing how much fun people were having with custom code, Myspace decided to run with it, turning the DIY experience from a bug (and security breach) into a feature.

“Users come first, and this is what they want” is a direct quote from one of the company’s then vice presidents. Could you imagine any Meta executive saying that today?

Myspace let users decorate—and showcase—their digital habitats, adorning their profiles with personalized HTML/CSS. It wasn’t the easiest thing to do, but the learning curve was part of the fun: People liked that they had to teach themselves to code to shape their in-app experience. People were proud of the work they put into designing their digital aesthetic.

People were so proud, in fact, that tutorials and how-to guides became part of the platform’s culture. Sharing and remixing templates became a social feature—a channel for connection and engagement. These user behaviors nurtured a sense of loyalty, enthusiasm, and kinship across the app.

As Facebook rose to power, though, Myspace scrambled to stay relevant. What was profitable—consumption, paid for by advertisers—simply didn’t work on a social platform that catered to customization and creation. Ads made an endearingly chaotic social canvas feel cluttered and impersonal, while Facebook’s streamlined algorithms nurtured our burgeoning, collective addiction to the infinite scroll.

Today, ads are a tiresomely tried-and-true business model, and consumption has become a finite resource. With every social platform competing to colonize our attention span, feature parity has become less about delivering the most value for your users, and more about prioritizing channels that manipulate engagement to artificially inflate likes, scrolls, and shares. Profit maximization has taken precedent over user experience—but those ad-based revenue streams are becoming increasingly saturated.

Meanwhile, creator/developer tools (e.g. Canva and Figma for designers; Framer for website builders; Lovable for full-stack coders; Glif for AI app builders) have built devoted community flywheels of target users who contribute custom-made goods across these in-platform marketplaces—whether templates, plugins, or full-stack apps. These digital spaces have figured out how to take the Myspace-style sentiment of ppl being proud of what they make and find a centralized place to distribute it TK and having that revenue cycle back into the platform.

But GenAI makes software easier to build than ever—democratizing the apps we exist on, and, more importantly, the revenue structures that drive them. Instead of optimizing for network effects and building for features that scale, the new era of software makers are taking inspiration from long tail content creators, and cultivating hyper-personalized software for a niche audience—one where community can be a feature, not a bug.

Come for the app, stay for the scene

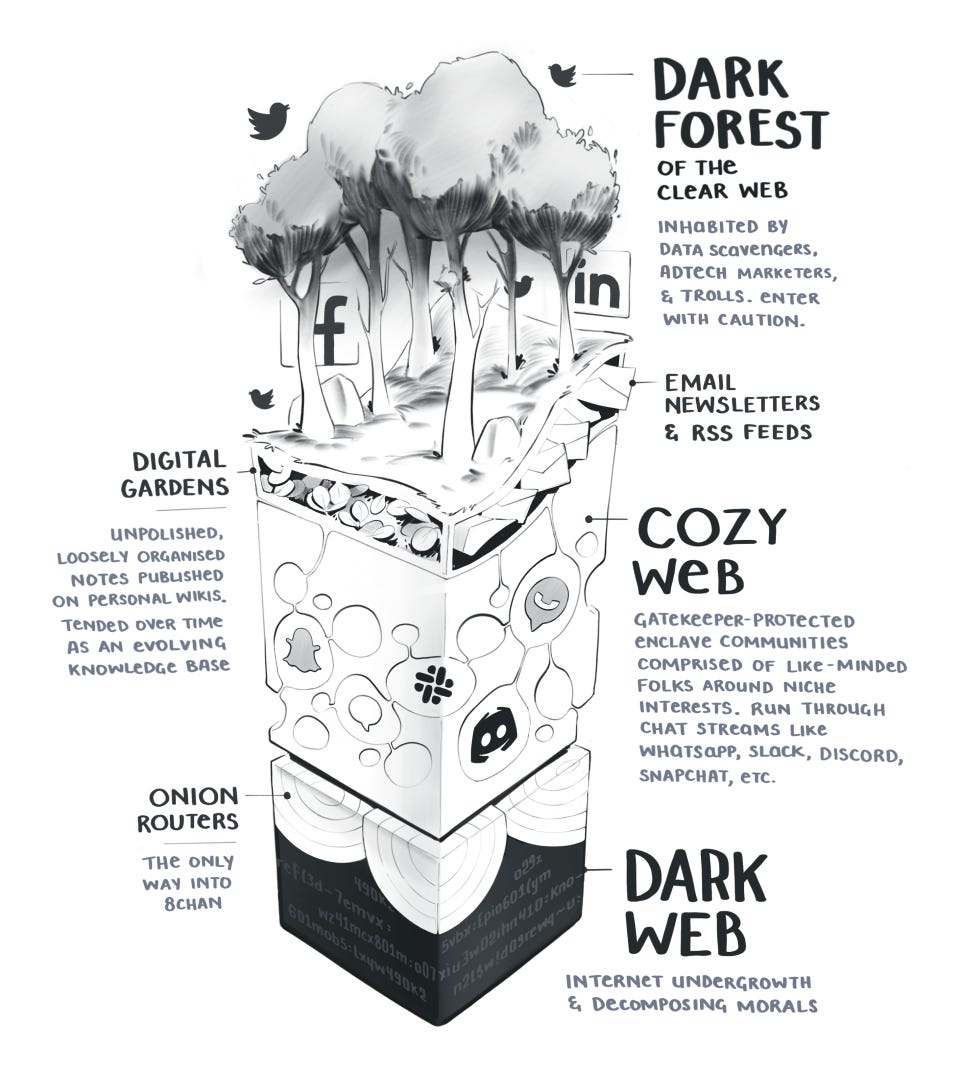

The rise of centralized social platforms like X and Facebook that keep and own our social data left people longing for smaller, quieter, intimate third spaces which offer reprieve from saturated algorithms.

In 2019, former Kickstarter co-founder and current Metalabel co-founder Yancey Stricker coined the Dark Forest Theory of the Internet: The notion that consumers are “prey” in an eerily still, digital forest, cosplaying as lurkers amongst the bot-generated comments and ad-cluttered feeds of today’s predatory social networks.

From this, Venkatesh Rao derived his cozyweb thesis, defined by discrete internet dwellings—niche, gate-kept channels like private Discord servers, community forums, and personal newsletters, which tend to be invite-only and shared first with IRL friends—like Myspace’s original inception.

Cozyweb conversation mediums may scratch the intimacy itch for social app purveyors, giving people autonomy over where they spend their time and who they spend it with, but they don’t hit the creativity fix that Myspace’s personal customization features granted.

Tools for thought—an upsert of personal knowledge management (PKM) apps—however, do.

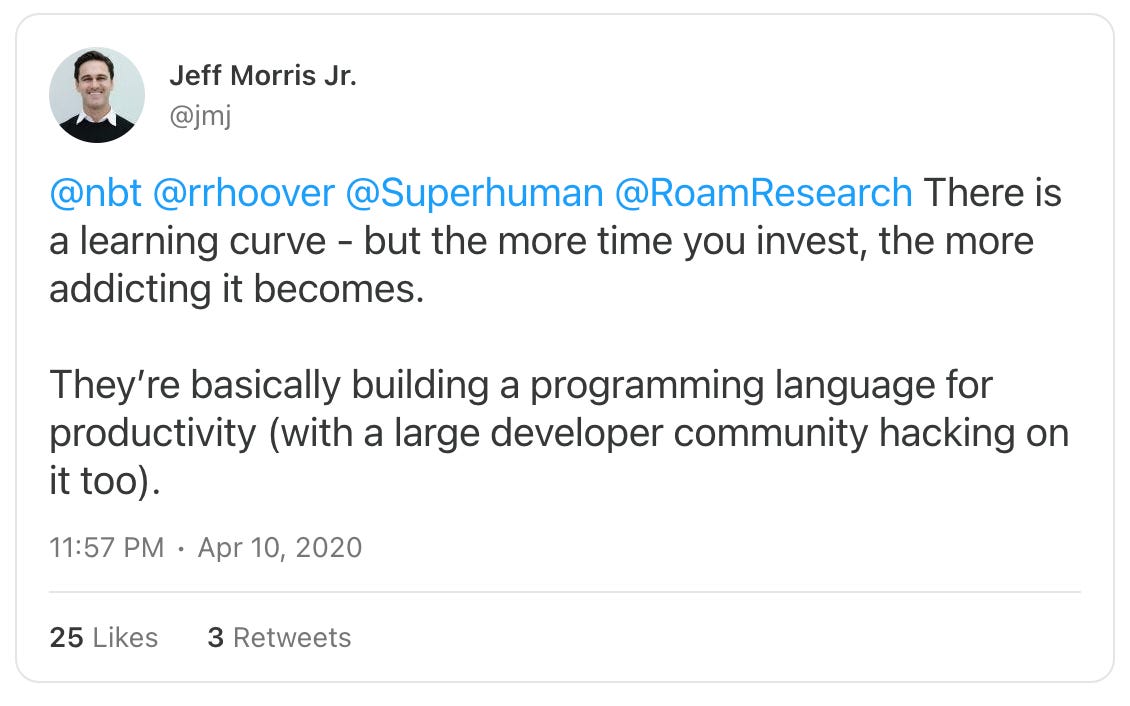

Platforms like Roam Research, Obsidian, and Notion, first conceived for, well, personal knowledge management, gained traction for the same reasons Myspace did. Pick-and-play features—like plugins and extensions—offer custom app experiences across the former in the same way that user-generated markups (used to) let people personalize their social profiles on the latter.

And, much like Myspace, the product learning curve is part of the fun. Friction to adoption instigates the same kind of devoted user base across tools for thought as it did for the social network: “The more time you invest, the more addicting [the app] becomes,”tweeted Chapter One managing partner Jeff Morris, who backed Superhuman and Roam, when productivity tools first started gaining popularity among consumers.

Users are similarly proud, too, of the work they put into customizing their in-app experiences: “How to use your [insert tool for thought]” videos are a dime a dozen; note-taking method Zettelkasten is now a buzzword; PKM “influencers” have become their own class in the ever-expanding creator economy.

And if we’re really stretching the definition of “productivity knowledge management” to include consumer LLMs, then ChatGPT slots into this equation, too: Three-time Chief Product Officer and former founder Claire Vo turned a custom GPT she built for herself into a subscription-based product management copilot in a single day.

Unlike Myspace, tools for thought can also participate in the platform upside of user-generated content (UGC). Like creator and developer tools, the most community-oriented PKM apps host bustling marketplaces where users can share, trade, buy, and sell customized app experiences created for and by a platform’s most dedicated devotees. Relational database manager Airtable allows you to develop and remix open source extensions; note-taking tool Obsidian boasts community-created plugins that add depth and/or breadth to your thinking process.

Community-generated contributions don’t just give users autonomy over their personal app experiences—they cultivate agency over the community itself. Lurkers become consumers become creators, generating a flywheel economy where the outputs of the marketplace flow back into the app ecosystem, as derived inputs.

Instead of conducting UX interviews or looking to the market for feature inspiration, the right contribution features mean your users get to dictate their own desire paths—their own hacks and tricks that custom-fit their customized app experiences. Often, those platform “cheat codes” are carried over from complementary apps, meaning that instead of going up against categorical competitors on feature parity, you can focus on consumer-directed integrations between apps across your users’ personal product stacks.

When you get the flywheel right, your most loyal users will literally build your app for you.

1,000 true fans 10,000 true power users

Tools for thought spurred the culture of community contribution—of community-led product development—and users are beginning to seek that feature parity across their entire consumer software stack.

Last October, The Browser Company (TBC) CEO Josh Miller announced the team’s move away from Arc—their flagship browser product—to focus on an app with more scaling potential.

No product embodied the “customization begets community” trend more than Arc did at its peak; if teenage girls were “uploading stickers” to their Myspace profiles before, today those commensurate Gen Z-ers are sticking Arc logos onto their Macbooks. From saving split-tabs, to custom color palettes, to easter egg UI animations, Arc’s value prop was quite literally personalization—and whether or not users found value in the pick-and-play features themselves, having the option to customize was enough to distinguish the browser against other product experiences across the market.

A (perhaps worrisome) byproduct of capitalism is that consumer software now manages to stir up the same cultlike fanship that D-list (F-list?) celebrities do.

That said, Arc doesn’t appeal to everyone.

Actually, that Arc “is a power user tool, and always will be,” is the very reason Josh cites for the company’s pivot. Whereas to consumers that’s a plus, the company’s $550 million market valuation demands a product powered by network effects—one that can scale to “1 billion users”. Instead of community being a feature, VC-backed business models turn indie culture on consumer apps into a bug.

What’s frustrating for users is that they want to pay.

Arc could be profitable today among their cult of power users, if TBC wanted it to be. In his response to the pivot back in October, software creator and Youtuber Theo talked about how reliant he is on both Arc and email client Superhuman—two incredibly niche software products with comparable valuations and massive user overlap. Whereas Arc comes free, Superhuman’s cheapest subscription costs $25 per month. Theo said he’d pay, albeit begrudgingly, $200 monthly for either product if he had to.

In the four months since the company’s pivot, people haven’t stopped frequenting Arc’s subreddit. Despite its makers moving on, its devotees are still loyal—and incoming. Not only are they desperate to keep using the browser—these power users actively want to contribute to its upkeep.

Last month, Theo posted an update, titled “I’m Finally Moving On (I have a new browser).” In the video, he goes over his criteria for a strong Arc contender; Vivaldi, with its vertical tab bar, custom quick commands, and “not shit performance,” among other factors, nails all six of his product criteria. What stops him from committing is that the team doesn’t prioritize user experience. “They don’t care about what users want,” Theo shares—the same feature request he has for Vivaldi now was first asked on their community forum two years ago.

Zen—an open source Arc dupe—is Theo's ultimate browser of choice. The team is “genuinely awesome,” their Discord is “super fun”, and the community is rallied around the right product goals: to make Zen the “best browser ever.” Not only is Theo contributing to their highest Patreon tier—he’s also taking it on himself to ship one of their developers a Macbook, to help them build better for Mac users like himself.

Theo summates the video by adding a seventh criteria to his dream browser: a team that cares.

BYOB (Build-your-own-bundle)

The great unbundling has made its way to consumer software. As remote work, creator economies, and knowledge industries merged into one melting pot of business-casual social graphs, PKM/workflow collaboration apps and design/developer tools have melded together in an increasingly murky slog of copy-cat feature sets and bloated product stacks. Whether dev tool Jam or multiplayer browser Tab, collaborative markups are a user requisite. Notion’s marketplace includes website templates that rival Squarespace’s—and AI-first presentation tool Gamma goes up against niche upstart deck-builder Pitch.com and Figma’s slides features…in addition to hosting a showcase of in-house landing page designs.

When Benedict Evans wrote about unbundled apps and smartphone interfaces back in 2014, he compared China’s Baidu Maps against the unbundled amalgamations of U.S. app stores. Baidu Maps, in this decade-old comparison, was the kitchen sink of search and discovery features, combining all the layers of Resy, Uber, and Yelp atop their map-based interface:

“You can find where a film is showing and choose a seat [on Baidu Maps]. You can order a cab, with cabs from all the services in your city shown together on the map and the order is going to be the best offer. You can book a hotel room or a cleaner.”

What’s interesting about this is that the map interface as the aggregation layer means that there’s a very specific niche of search and discovery features that the app is (or was) looking to integrate: those catered to location-based, typically social activities. Says Benedict, “Baidu can make a maps app that’s an order of magnitude better because it contains within itself every possible maps-based use case, and nothing more.”

Ten years later, Granola’s Chris Pedregal is echoing a similar sentiment around AI-native consumer apps: go narrow, not wide.

For the first time, the marginal cost of software development favors the longtail—it’s actually more advantageous to cultivate cult-like products that don’t scale, than try to penetrate market share against incumbents. Unbundled apps competing across the consumer Saas ecosystem don’t have to worry so much about going head-to-head on feature sets; they can instead customize their product experience around a singular user persona, focused on consumer-led depth versus market-driven breadth.

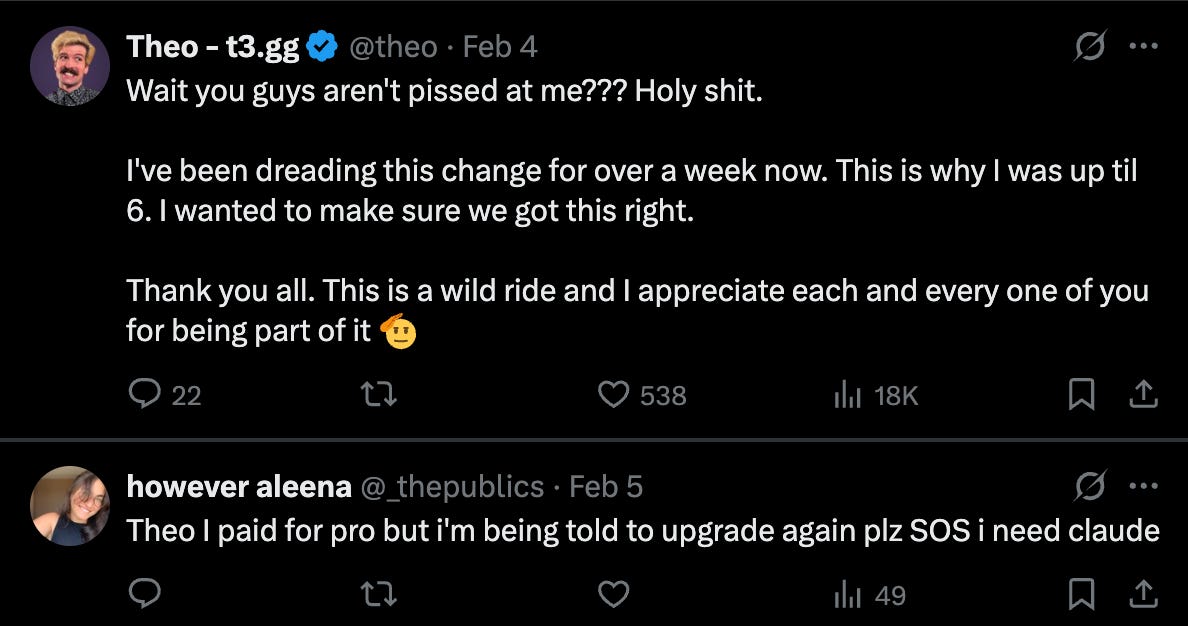

Not only are consumer app monetization models going by way of the creator economy. The inverse is happening, too. Content makers are getting into consumer Saas—and bringing creator-oriented business models with them. I’ve long ditched both my Claude and ChatGPT chatbot subscriptions in favor of aforementioned software Youtuber Theo’s t3.chat, which is cheaper and allows me to pay patronage to a creator I learn from, with more consumer utility than access to exclusive content through Patreon might grant me.

When Theo had to change his paid pricing structure recently due to API costs, he stayed up until six in the morning making sure he got it right for his subscribers—and uploaded a video sharing his reasoning, nailing two revenue channels with one product update. His performance is authentic, but what’s more important is that, like Zen, Theo really cares about his users. When fans-turned-consumers took the news well, he expressed both shock and gratitude for his followers.

Indie developers like Pieter Levels have been making money through monetized micro-apps for years now, paid for by an almost-concentric Venn Diagram between target users and stans (super fans) on X.

And with the democratization of prompt-first coding, spinning up software from scratch and charging for it means that everyone has access to a career as a personalized software creator.

Your biggest competition may no longer be the market: They may be your target users.